Below is a speech by Gundagai Independent Publisher Pat ‘Scoop’ Sullivan delivered at the 2001 Maher Cup reunion at Tumut. The 400 strong crowd responded with a rousing ovation. Scoop’s talk was edited and published in the Tumut & Adelong Times on 6 November 2001 – from which it is reproduced below.

Sadly ‘Scoop’ passed away in 2015. His talk vividly illustrates why he is such a loss to the Maher Cup community. At the 2016 reunion at Cootamundra Barry Madigan read Scoop’s words to a most receptive crowd. Here they are, with some images added:

Fanaticism, Folly & Fights Surround Famous Trophy

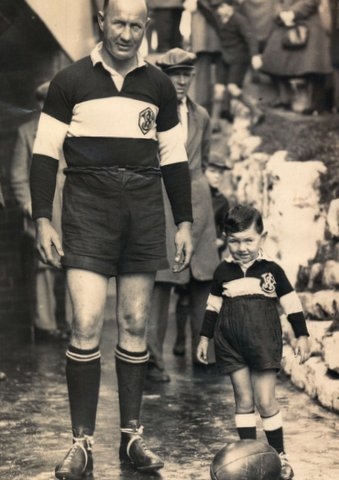

My earliest Maher Cup memory is still one of my most vivid. I was only a wee fellow. The year was 1951. Gundagai challenged Cowra for the Cup, and beat the Laclansiders by the one point.

Max Ibbotson refereed the game and Rouse Boyton was one of the touch judges. There was one of those controversial goal decisions. Jack Cudmore, Cowra’s skipper, took a pot at goal. One flag was up, and one down, and Ibbotson ruled in favour of Gundagai.

At game’s end a female fan attacked Rouse Boyton with an umbrella and the biggest brawl I have ever seen was on. It seemed to my eleven year old eyes that some 832 people were involved, but perhaps it was only 823. Max Ibbotson, the much reviled referee, was travelling in our car, the car of my late boisterous uncle Jim.

We had to pick Max up from the rear of a pub and we received a police escort out of town as the good citizens of Cowra hurled insults and missiles at us.

Such was the fanaticism which the Maher Cup inspired. Normally sane and respectable citizens became foaming at the mouth ratbags, for Maher Cup madness was indeed an identifiable disease.

And the Maher Cup could make strong men weep. Many of you will recall Bruce Maitland, president of Barmedman club and a Group administrator of long standing. Barmedman once challenged Gundagai for the Cup and seemed to have the trophy in their keeping until Bronc Jones landed one of those prodigious long range goals for which he had such genius and made it 4-all, enabling Gundagai to keep the cup.

I was astounded to see great big salty tears coursing down Storky Maitland’s handsome visage. But that’s the effect Maher Cup mania produced.

Football not only inspired fanaticism, tears and violence, it also led some people to prayer. I remember when one of our hosts tonight, John Madigan had his rosary beads out, spitting out Hail Marys at machine gun like speed, as Harden took an after-the-bell penalty for a win. The power of prayer did not prevail on that occasion.

The Maher Cup story is packed with fascinating football facts, but it is also packed with legend and myths which have grown over the years. When Tumut hotelier Ted Maher donated the cup way back in 1920, he could have had little idea that this was to become the most coveted and famous of all football trophies in country NSW.

Maher Cup football was the toughest. It was a grand final every week, for each week the Cup was either won or lost. Even a draw meant a loss for the challenging team.

Club officials looked on the Cup as the horn of plenty of Rugby League, cash cascading from it. And for players, it was honour and glory, and a chance for a special place in a club’s history. For fans, there was the vicarious pleasure of seeing your town’s sporting idols belt the socks off some other town’s hopefuls.

The Cup itself cost just 15 guineas – but it became the centre of rows and ructions which cost thousands, in one case at least even leading to an action in the NSW Supreme Court, when Harden and Cootamundra became desperately serious about who owned the Cup.

At first it was a rugby union trophy, but as rugby league took over the territory it became a challenge trophy first played for between Gundagai and Tumut and later spreading to the old Group 9 area. Even in those earliest days it had crowd pulling power, with reports saying over 1000 spectators were present at a match between Gundagai and Tumut in 1922.

Cootamundra entered the lists and became possessor of the cup, winning it outright, and then altering the rules to suit itself and make sure Coota had first and last challenge every season.

Then Wyalong, inspired by bad Bill Brogan, took the cup in 1925. Temora and the invincible Eric Weissel then came into Cup history and then Young and June, and the mania began to spread like wildfire.

A dispute between Gundagai and Coota in 1925 led to a new Maher Cup rule — no club holding the cup was allowed to receive or entertain a challenge from Gundagai!

And Temora did not trust Coota. In 1925 Temora offered a £1000 bet – a whopping large amount in those days – to say Temora could beat Cootamundra, providing a neutral ref – nominated by Temora of course – was in charge.

They were a little madder in those days. At one stage they even introduced a rule that coaches couldn’t play, and Temora refused to play Young because Young wanted their coach on the field.

Crowds were spoken of as being 4000, travelling by special trains, sitting on benches on the back of trucks, getting there any way they could.

Protest became a word naturally associated with the Maher Cup.

In 1929 when the cup went to Junee after Coota had played unqualified players, Chips Phillips and Sid Harris, the cup was sent to Junee in a box labelled “Maher Cup on loan to Junee, home of the squealers”.

Since then it has been locked in jails, chained to anvils and once tossed down a storm water drain.

The Maher Cup was ever a venue for big betting, so it was no surprise in 1938 when a referee, one Mr Murphy of Sydney, declared an attempt had been made, by Cowra supporters, to bribe him so they might beat Young. The ref walked off before the game was over and it led to another almighty blue with the ref saying he refused to referee a fight.

The poor old press got the blame. The judiciary committee sat on the bribery case and found that the trouble had been caused by the press reporting the incident, saying the press was “to be deplored”.

Betting was always associated with the Maher Cup with huge wagers being placed by colourful figures like Phil Michael of Temora and Lou Moses of Harden. Many a player found his bonus boosted by donations from grateful punters. “How much start is Moses offering? What price is Michael betting”. They were common questions on Maher Cup morning and small fortunes were regularly won and lost.

Referees like Max Ibbotson, Charlie Gardiner, John Livermore, Leo Boyton and Blue Curran had their special place in Maher Cup history, often as the centre of controversy or the target for abuse. Refs continually received the blame for defeats. When the Maher Cup era was coming to its end, Wagga Magpies challenged Gundagai for the cup. Pies were led by form Australian captain Arthur Summons and they were odds on favourites.

I met Arthur at Gundagai races one day and said it was rare indeed to see him in my lovely home town. “I haven’t come back here since we challenged for the Maher Cup. I vowed never to return,” said Arthur. “If ever we knew where we were at the kickoff it was that day. “Nevyl Hand was refereeing and David Hand was playing prop for Gundagai. We kicked off, David Hand moved inside the ten yard mark and took the ball. “I was waiting for the whistle to blow, but Nevyl yelled out “Go son!”

Nevyl Hand’s Gundagai Tigers had established a record of 23 Maher Cup wins in a row in 1951 and 52, with a team which many declared was the best ever. Those years of the 50s were a gold era for Group 9 with many clubs, notably Young, Wyalong, Cootamundra and Temora, also fielding teams which produced a brand of football not seen before or since. It was almost compulsory to be an international to get a coaching job in Group 9.

But the same era threw up many grand local players as well. Could you ever forget that majestic lock forward Peter O’Connor, or Len Henman, John Ryan, Allan Glover, Noel Bruce, Ron Crowe, or Bruce Powderly?

Towards the end of that golden era, in 1959, Harden Murrumburrah began a record breaking run which will ever remain. The team held the cup for the whole of the 1959 season and for 11 matches in the 1960 season until beaten by Tumut 8-4, Bernie Nevin, who is here tonight, scored 136 points in Maher Cup games that season, breaking the 25 year old record of 115 points established by the mighty Tom Kirk. And Nick Cullen, who is also here, played in every one of those Maher Cup games.

The nuttiness peculiar to Maher Cup football continued however, Harden led 14-5 against West Wyalong when the game was called off by referee John Livermore. He had sent off Col Ratcliffe, following an altercation with Bernie Nevin. Wyalong officials were calling upon Col to bring the rest of the team off with him, but he refused. Moments later Ron Cooper of Wyalong was sent off. Some Wyalong players went off in sympathy and only eight Wyalong players were on the field as Harden’s Frank Todd kicked a penalty goal. Only two Wyalong players lined up for the kick-off and the match was abandoned.

That record breaking Harden team had many great players, fellows like Eric Kuhn, Kevin Negus, Matt Grenfell, and a real speedster in Gerry Robinson.

But I confess that my favourite players in the side were Tom Apps and Lindsay Ellison always did like my footballers big, fat and ugly.

Ah yes, the Maher Cup tale is a long an involved one, impossible to cover it all in a single night.

Madness certainly abounded. In 1952 to crowd at Gundagai-Young game at Anzac Park refused to leave even though the floodwaters of the swollen Murrumbidgee were cutting off access to the ground. Eventually, a pontoon bridge had to be hastily thrown up to get the estimated 4000 fans over the murky waters. Would it happen anywhere else but at a Maher Cup game?

Many great players played for the Cup and many great characters were among them. I think of Fred De Belin, Gubby Allan, Ray Beavan, Ted Curran, Johnny Kelly, Baden Broad, Bede Madigan, Father John Morrison, Doug Cameron, Sid Hobson, Mick Jones, Ray Green, Bobby Downing, Toby Barton, Frank Farrington, Jack Gibson, Father Peter Quirk, Bill Longhurst, the Lawrence family of Barmedman, Darrell Fazio, Bill Kinnane, Ian Sheather, the incomparable Eric Weissel, Peter Diversi, Ike Fowler, Clem Kennedy, John Ryan – the list seems to be endless.

But not only players became Maher Cup legends. In Gundagai, one of the greatest of Maher Cup legends was the late Dudley Casnave, who never played a Maher Cup game in his life. But Dudley was one of those fanatical supporters. One day, almost fifty years ago, Gundagai were defending the cup against Wyalong. Wyalong’s long striding winger, Clive Lemon, broke clear and was scooting in for a try, not a defender in sight. Out of the crowd came Dudley, his army greatcoat billowing about him, to execute a flawless tackle on the Wyalong speedster to the delight of the large crowd.

Sadly, the Cup did not last forever. In the 1960s disgruntled administrators forced boundary changes – the Murrumbidgee Rugby League rebellion took out the old cup teams and others were scattered into makeshift competitions.

When rugby league peace was restored a new Group 9 was created in which many of the clubs, the Wagga sides, Batlow and Tumbarumba had no real Maher Cup tradition. Interest waned, challenges became few, until in 1971 Tumut played that last game to lift the cup from Young. And the famed prize now rests here in the Tumut Old Boys cabinet. It’s fitting that its final home should be in Tumut, where it all began. [Editor’s note: the Cup was relocated to the NRL Museum in 2013; and returned to Tumut in 2019 where it resides in its display cabinet at Club Tumut]

Maher Cup players are getting no younger, many of that great golden era have answered the final siren.

It was a Harden coach, Harry Melville, who had played with the mighty St George, who declared after one Group 9 season: “I don’t want to come back here, this is the toughest football ever.”

When I think of those glorious and tumultuous years my mind keeps turning to two players who for me epitomised Maher Cup football, those old Barmedman stalwarts Col Quinlan and Rusty Gorham. They were men who gave no quarter on the field, who played it uncompromisingly and ruggedly. But off the field they had that marvellous gift of mateship. I don’t think they had an enemy off the field. On the field they certainly had no friends in opposition jerseys.

Barry Madigan, Maher Cup player, eloquently presenting Scoop’s speech. Source: Cootamundra Herald on Facebook

Where are they now? Do old Maher Cup players go to heaven? Of course they do! But they don’t go to the harping or singing section. They go to a place where the music comes from the rattle of sprigs on concrete as teams take the field, where the scent of heavenly gardens is replaced by the sharp smell of liniment wafted on a winter breeze, and where the adoring multitudes burst into waves of cheering as the whistle sounds, a boot hits the ball, and the greats of the misty past enjoy their own heavenly delight.